Genealogy VERSUS GENETICS

The Keys to Our Identity

by Joelle Steele

For many years, I have taught a genealogy research class through the adult education departments of several community colleges in the South Puget Sound of Washington state. One of the reasons why many students attend these classes is because they have come up against a stumbling block – or a very big wall – in their research.

For many years, I have taught a genealogy research class through the adult education departments of several community colleges in the South Puget Sound of Washington state. One of the reasons why many students attend these classes is because they have come up against a stumbling block – or a very big wall – in their research.

The most common kind of scenario was one in which a student's grandfather had come to the United States from a country such as Finland, and his descendants always referred to themselves as Finnish "on Grandpa Henry's side of the family." But the student couldn't find the city that Henry came from in Finland. The student then decided that Henry probably wasn't Finnish after all and sent away for his own DNA profile.

When the student got their DNA profile it said they were 5% Scandinavian, 19% Eastern European, 43% Southern European, 9% Ashkenazi Jew, 14% Celtic, and 10% Finnish/ Saami. The student then assumed that Henry couldn't have been very Finnish after all. But Southern European? Where did that come from?

For the most part, the answer is simple. Genealogy and genetics are two very different things. Genealogy is about nationality and the history of the people who form multiple generations of a family. Genetics, on the other hand, is about the chemistry of the biological make-up of a living entity, whether it's a human, a dog, a fish, an insect, a plant, etc.

DNA is ancient and it predates any genealogical history a person may have, because DNA goes back not hundreds of years, not even thousands of years, but millions of years, back to the earliest living humans. In other words, genealogy is about the origins of a family; genetics is about the origins of humankind.

When the student in the example couldn't find Grandpa Henry's hometown in Finland, that could be because it had a Finnish name that is now spelled differently, the name could have been in Swedish or Russian if the town was near the Russian border, or it could have been given a Russian name when Finland was still a Russian duchy up until 1917/18.

When wars and politics are involved in a particular part of the world, it's important to know something about the history of that area, because borders are often re-drawn and nationalities can change overnight. That's why it's important to not let a country define a person, even if a family has lived there for ten generations. That nationality is only a part of a person's history. DNA is the other part.

Human DNA is divided into 23 pairs of large parts called chromosomes. The 23rd pair determines whether a person is male or female. Each chromosome is divided into smaller parts called genes. Each chromosome can carry hundreds or even thousands of genes.

The genes determine how a body grows and functions and are responsible for the color of skin, hair, and eyes; height; face shape; face features; susceptibility to certain diseases; tastes for certain foods; athletic ability; etc.

The genes also determine ethnicity since some are found only in certain groups of people. This indicates where a person's ancestors once lived tens of thousands to millions of years ago. The autosomal method of DNA testing is used to determine the combination of different ethnicities carried in a person's genes.

When it comes to DNA, many people are surprised, some utterly shocked, at what their genetic profiles reveal about their biological ancestry. This is because their DNA usually forms a less-than-perfect match with what they know about their national origins.

I'm half-Italian from my father's side and half-Swedish-Finn from my mother's. But, this doesn't mean much when I look at my DNA profile. It tells a very different story.

Among other things, my DNA says I'm 30% Finnish, Saami, and Siberian. It shows no Scandinavian DNA at all, yet my mother was a Swedish-Finn.

DNA proves that no one is ever a "pure" anything. Today's Swedish-Finns are the descendants of Swedes who settled on the Finnish frontier several hundred years ago. They intermarried with Finns and Russians at various times in history. But Finns are not genetically the same as Scandinavians (Swedes, Norwegians, and Danes).

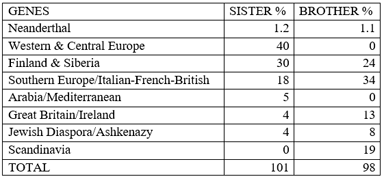

My brother's DNA is very different than mine. His shows that he is 19% Scandinavian and 24% Finnish, Saami, and Siberian. We have several other differences as well. For example, I am 5% Arabic; my brother has no Arabic DNA; and I am 40% Western and Central European, and my brother has no DNA from those areas. However, we both share small percentages of Ashkenazi Jew and Celtic genes.

This brings up the question that many people ask when it comes to the DNA of their siblings:. Why is it so different? – and it always is. Most people assume that if they have their DNA profile done that their sibling's DNA profile will be the same. After all, they do have the same parents.

But DNA profiles of siblings are different because every time a child is born he or she carries DNA from both parents, but each sibling carries it in different amounts and combinations.

This re-shuffling of the parents' DNA is called genetic recombination (recombinant genes). That means that, on average, siblings share only about 50% of the same DNA. And, in fact, that is the exact amount that my brother and I have in common.

This difference in shared genes is what also determines how much family members resemble each other. It may seem like all families share some family resemblances, but actually they don't.

I am a court-certified expert in face and ear identification. That means that I measure faces of people in photographs to authenticate their identities. I have worked on many family photo albums trying to identify the people in the photographs. In some cases everybody looks alike in some way or another. In other albums, it is just the opposite. The siblings don't look alike and they don't always look like their parents either.

My brother and I do not look that much alike. I look like my Italian father, who looks like his mother, who looks like her father. You have to go back all the way to my great-grandfather on my mother's side of the family to get a glimpse at the origins of my brother's face.

For those with European and North American ancestry, DNA is considered to be quite accurate. But for the rest of the world, DNA is a lot less specific because there are far less DNA samples available to use for comparison and classification of DNA. That means that the DNA profiles for people who come from Africa, China, India, South America, etc., are not nearly as detailed as they are for Europeans and North Americans.

The important lesson about genealogy and genetics is that humans are extraordinarily complex. We are part history and part biology. Taken separately, neither means as much as does the combination of the two. And that combination is the key to our identities, to who we really are.